2D Materials – A quest for clean water

Research 26 October 2017

Our quest to help make seawater drinkable leads to a scientific discovery we weren’t expecting – salt ions that can change shape

Desalination of seawater remains one of the most challenging and expensive ways to produce drinking water. But as water scarcity forces communities in many parts of the world to find new sources of drinking water, our international research team based in The University of Manchester is committed to making a breakthrough in this critical field using our world-leading expertise in materials science.

This quest has inspired us to develop ambitious experiment. Not only has our Manchester-led team created the smallest possible man-made slits in a bid to perfect the desalination of seawater, our pioneering filter also produced a shocking result – we revealed that large salts with ions considerably bigger than the slits were still able to squeeze through by flattening their shape.

That is because these ions apparently behave like soft balls – for example, like tennis balls which can be squeezed into a different shape – rather than hard balls, such as billiard balls which are very rigid.

Our study began when we succeeded in creating slits that are just several angstroms (Å) – one ten-billionth of a metre or 0.1 nanometre in size – and we investigated how ions pass through such ultra-confined structures.

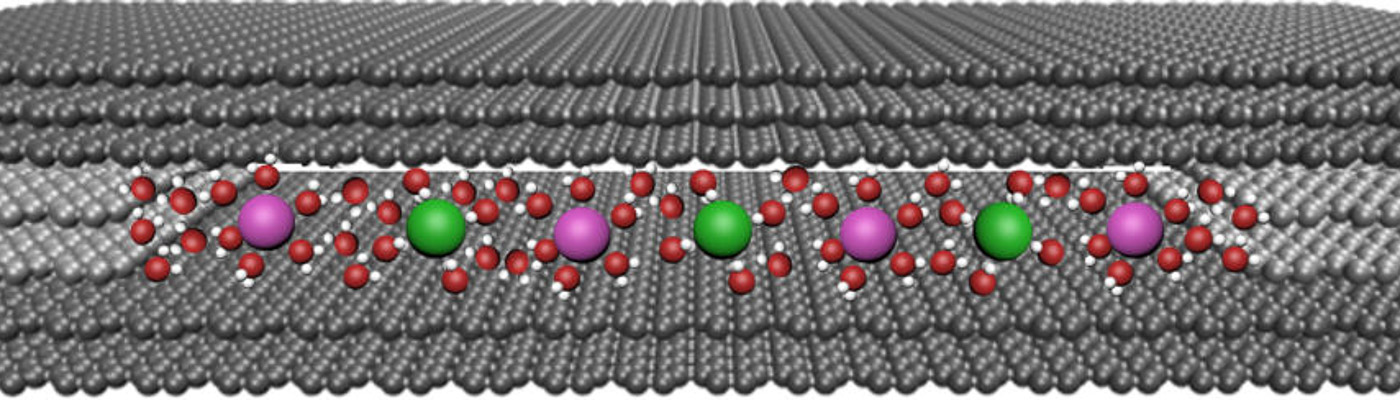

These slits are the smallest possible man-made holes. They were painstakingly created from various 3D and 2D materials, including graphite, graphene, hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) and molybdenum disulphide (MoS2) and, surprisingly, they allowed ions with diameters larger than the size of the slit to permeate through.

Ions behaving like squashed tennis balls

For example, the bigger ions such as Al3+ (aluminium ions) moved through more slowly than smaller ones like K+ (potassium). Under closer examination our team discovered that the larger ions were able to distort the ball-like configuration of water molecules around them – their so-called hydration shells – to squeeze through the slit.

The classical viewpoint is that ions with a diameter larger than the slit size cannot permeate – but our results show that this explanation is too simplistic. Ions in fact behave like soft, tennis balls rather than hard billiard balls – and large ions can still pass through, either by distorting their water shells or maybe by shedding them altogether.

Although the exact details of this mechanism remain to be understood we believe that ions with a diameter twice as big as the slits’ heights are still able to pass through. However, ions that are much larger (ie bigger than 13 Å) were not able to compress their shells to the extent required and were therefore successfully blocked.

Positive and negative ions behave differently

And that was not all. There was another surprise in store for us after we found that anions (negatively charged ions) and cations (positively charged ions) with the same diameter pass through the slits at different rates. In the case of K+ and Cl– (chlorine) ions for example, Cl– ions move slower than K+ ones.

We believe this is because anions interact more strongly with the graphene and hexagonal boron nitride walls compared to cations of the same size. This results in extra friction of Cl– ions against the walls, which thus reduces their mobility.

Again, more work will be needed here to fully explain what is happening – and we will probably be using computational modelling, such as quantum Monte-Carlo simulations, for example, to understand how ions interact with graphene and the hBN walls.

These new findings will help our team better understand how angstrom-scale biological filters such as aquaporins work and so will help in the development of high-flux filters for water desalination and related technologies, the Holy Grail in this field of interest. Success will help meet the global challenge of satisfying the exponential demand for clean drinking water.

Nature abounds with examples of materials that contain angstrom-sized pores which can rapidly transport selected ions and molecules through membranes. Aquaporins, for example, are proteins containing channels that are just 0.3 nm wide, can transport water at extremely high rates and also desalinate.

Researchers have been trying to mimic such ion transport systems for a number of years, but this has proved to be no easy task. Channels fabricated with standard lithography techniques and conventional materials have unfortunately been limited in size by the intrinsic roughness of a material’s surface, which is usually at least ten times bigger than the hydrated diameter of small ions.

Although “smoother” nanoscale ion transporters, such as those made from carbon and boron nitride nanotubes; nanopores in monolayers of MoS2; and graphene have proven to be better for reducing roughness, they are still too big. What is more, they contain too many defects and are electrically charged, which makes it difficult to figure out whether ion transport occurs as a result of this charge or if it is limited purely by the size of the channels themselves.

Creating chemically inert filters with smooth walls

So, to better understand the fundamental mechanisms behind ion transport, our team made atomically flat slits measuring just several angstroms in size. These channels are chemically inert with smooth walls on the angstrom scale.

We made the slit devices from two 100-nm thick crystal slabs of graphite measuring several microns across that we obtained by shaving off bulk graphite crystals. We then placed rectangular-shaped pieces of 2D atomic crystals like bilayer graphene and monolayer MoS2 at each edge of one of the graphite crystal slabs before placing another slab on top of the first. This produces a slit between the slabs that has a height equal to the spacers’ thickness (around 7 Å).

Basically, it was like taking a book, placing two matchsticks on each of its edges and then putting another book on top. This creates a gap between the surfaces of each book with the height of the gap being equal to the matches’ thickness. In our case, the books are the atomically flat graphite crystals and the matchsticks the graphene or MoS2 monolayers.

Smallest slit size possible

The assembly is held together by van der Waals forces and the slit is roughly the same size as the diameter of aquaporins. It is, in fact, the smallest slit size possible since slits with thinner spacers using just one layer of graphene are unstable and collapse because of attraction between opposite walls. The slits are also extremely clean and do not contain any defects because they have been shaved off from high quality bulk crystals.

Ions flow through the slits if a voltage is applied across them when they are immersed in an ionic solution, and this ion flow constitutes an electric current. The team measured the ionic conductivity as they passed KCl (potassium chloride), CaCl2 (calcium chloride), AlCl3 (aluminium chloride) and other chloride solutions through the slits and found that ions could move through them as expected under an applied electric field.

It was this analysis which revealed that the bigger hydrated ions moved through more slowly than the smaller ions because they were distorting their hydration shells.

This was a breakthrough experiment for a number of reasons. In fact, some in the team couldn’t sleep for a couple of nights after we had made these exciting and unexpected discoveries. Of course, the work continues and we have more investigations to make following this study’s interesting results – but we are confident we are a step closer to the high-flux filters that will meet the global challenge of desalinating seawater for those communities desperately looking for new sources of drinking water.

- The research is detailed in Science. As well as The University of Manchester, the team also includes scientists from the University of Science & Technology of China in Hefei, the National University of Singapore, and Southwest Jiaotong University in Chengdu.

- Sir Andre led the research group which included Manchester postdoctoral researchers Dr Ali Esfandiar and Dr Gopi Kalon that has published a breakthrough paper in Science.

2D MaterialsgraphenemembranesNational Graphene InstituteSir Andre Geim