Exploring Sellafield’s limitless future

Blog 11 October 2019

Author: Petra Tjitske Kalshoven, Dalton Research Fellow, School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester

Whatever it might do otherwise, one thing is clear: the Sellafield site sparks the imagination. In June and July of 2019, an interdisciplinary research team at The University of Manchester organised three workshops in Whitehaven, West Cumbria (10 miles north of Sellafield), to ask what the site could be, or mean, or do, once decommissioning would have finished in 120 years’ time.

Under the banner of ‘Sellafield Site Futures’, our aim in this research project was to ignite a debate about possibilities (societal, technological, ecological, aesthetic) for place making in the future. The project also aimed to generate research questions meant to enrich scenario modelling in contexts of uncertainty.

Lively conversations took place on themes of art and heritage, technology and science, and ecology and landscape. Participants were drawn mostly from West Cumbria—some affiliated with the nuclear industry and its supply chain, others active in the arts and heritage sectors, yet others engaged in cultural and ecological initiatives.

Background

Sellafield Ltd (SL), the company running the nuclear facilities on the Sellafield site in West Cumbria, is moving into full decommissioning.

There will be a lot of activity on site for years to come as ‘legacy’ buildings are taken down and others are constructed to make this happen. The changing skyline, with legacy chimneys becoming shorter and shorter, is testimony to this transformation and constitutes a conscious effort on the part of the company to show that change is underway.

With SL being the major employer in the area, decommissioning happens amidst local doubts about alternatives for a prosperous future. The process of environmental remediation, however, will be slow: decommissioning is planned to be completed by 2140.

Workshop themes

The workshops, in the intimate setting of the Barn at Rosehill Theatre with views opening up to embrace the Irish Sea, facilitated imagining and exploring possible ‘end states’ for the Sellafield site post decommissioning, 120 years into the future, going beyond immediate socioeconomic concerns.

We emphasized that we would not be able to come up with any answers—the issue of end states will be revisited again and again over the coming years. But what we could do at the workshops was think about questions that need to be asked and things that need to be known in order to take steps moving forward.

So we asked participants to draw on their current hopes, desires, experiences, and creativity whilst indulging in what we could perhaps call reasoned attempts at science fiction.

Questions included:

- What might the site look like in 120 years’ time?

- What might be possible in terms of use and occupation, depending on the level of decontamination effected by 2140?

- What legacy is the site to leave—material, virtual, conceptual—as a physical place, as a habitat, or as a place projecting specific meanings?

- What opportunities might the site afford in a wider area with conflicting economic, political, and historical interests; where a variety of stakeholders, species, communities, and habitats are involved; and where societal arrangements and moral frameworks, ways of living and working, might look very different in the future?

- And why would the future of these ‘20 acres of farmland’, as one participant put it, matter at all, once decommissioned?

Discussion

Questions like these led us into discussions of material and immaterial heritage, social, intergenerational, and environmental ethics, and the past as a catalyst for the future, themes that we kept revisiting over the course of the workshops.

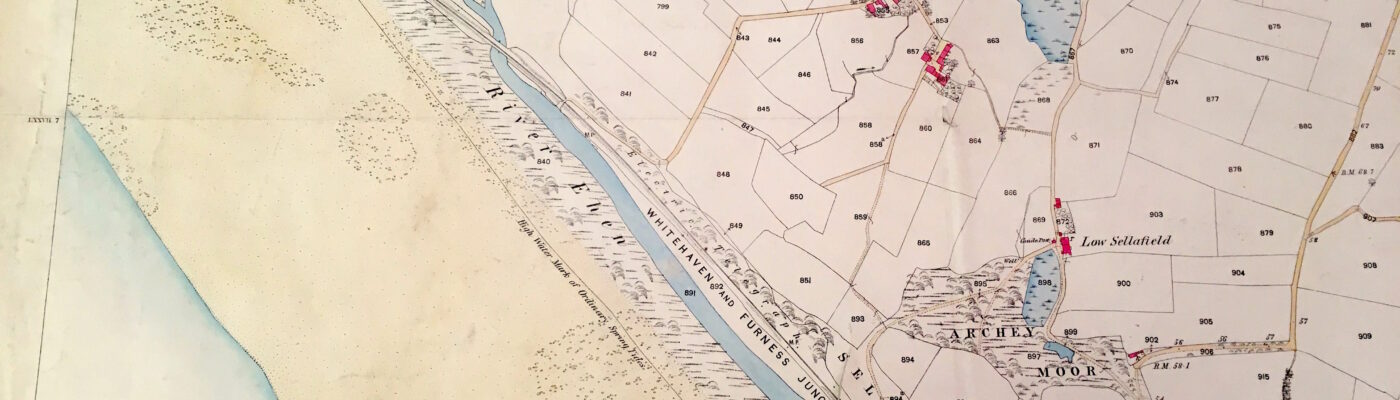

Reacting to short invited talks and presentations, sculpting scale models from playdough, and poring over maps of the area, old and new (which turned out to be excellent conversation starters), most participants showed themselves quite keen to somehow preserve the site for future generations.

Importantly, this was not about its memory only. Participants suggested keeping the site in a more tangible way: virtual reality might be a useful tool, but the sheer materiality of the site was considered important to hold on to—perhaps, it was suggested, some of the iconic buildings could be kept.

In any case, the site’s interesting and contentious history was considered worthy to be carried forward into the future, a source of pride for some: because of the milestones in nuclear science and technology that had played out on site, the socioeconomic role of the nuclear industry as a major employer, and because of family connections—a monument to human hubris to others: because of its association with secrecy, the military, and hushed-up incidents.

Some large maps had been commissioned for the workshops for use on the floor, to be walked on—which to our surprise evoked the lack of accessibility of the actual site amongst participants who were not affiliated with the nuclear industry and longed for a stroll in that forbidden land.

Context

One aspect that emerged quite strongly at the workshops was the importance of context. We started out talking about the Sellafield site as a neatly delimited geographical area, but it seemed to make more sense to conceive of the site as a porous area, spilling over into its surroundings, as part of the wider context of West Cumbria, with links extending outwards—historically, now, and into the future.

A ‘Sellafield board game’ had been specifically developed for the project by members of our research team to allow players to explore such links in a playfully competitive setting.

We tried out the game at one of the workshops, with pairs of players representing a socioeconomic body or a (regional or national) institution with stakes in the area. Whilst each pair pursued its own goals to position itself for a win (with at least some attempts at collaboration!), our game master introduced challenges that threw the players off course, making for an uncertain future.

Uncertainties

And that brought us to an inventory of uncertainties, unknowns, and unknowables. What would we need to know to plan for possible end states? What is uncertain, and what will remain uncertain for years to come? What do we not know, and what can’t we know: what is unknowable? How do we acknowledge uncertainties and unknowables and work with these, rather than smooth them over?

Follow Up

For now, our Sellafield Site Futures project remains almost as open-ended as its subject matter. Besides working towards publications and more research questions, we continue developing the board game (which we think may actually be most interesting in a liminal state, never completely finished).

Another tangible project output will be an artwork emerging from the discussions that we had. Throughout the workshops, and preparing for these, we had Cumbria-based artist Wallace Heim thinking along, and ahead to a tangible expression of what she observed.

Sellafield Site Futures, then, whilst still remote, will emerge from this project in writing, in gaming, in artistic expression, provoking continuing debate on how to imagine, and shape, a place of continuing fascination.

Leave a Reply