More than 70 years after the Enigma was cracked by Alan Turing and his colleagues at Bletchley Park, innovative technology housed at The University of Manchester has provided a detailed peek beneath the bonnet of the German wartime cipher machine.

A deadly weapon

The German Enigma machine was integral in providing the Axis powers with the upper hand during World War II – particularly during the Battle of the Atlantic. At this time, the UK was extremely reliant on imports from the US and Canada to keep the population going and fighting. However, German submarines were used to form a blockade and stop these supplies getting through. Crucial to the Axis efforts at this time were the Enigma machines that allowed them to share classified information secretly by encrypting it.

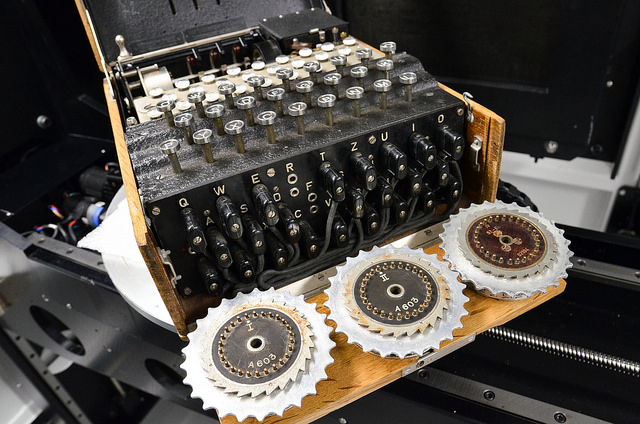

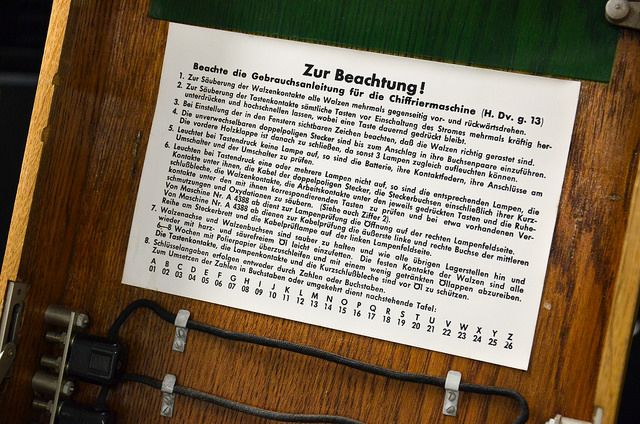

While it might look like a clunky typewriter, the Enigma machine was very good at its job. The machines had a typewriter keyboard to input the messages and a light board that would spell out the encrypted version. Each Enigma operator had a book of codes – a different one for each day – which instructed them on how to set up the machine for that day.

Once a coded message was produced by one machine, it was sent via Morse code to an Enigma operator based elsewhere. That operator would use the same daily key code to set up their own machine in the same way, and they could then simply input the cyphered text on the keyboard. The light board would display the actual message, which would be copied down by the operator.

Indecipherable

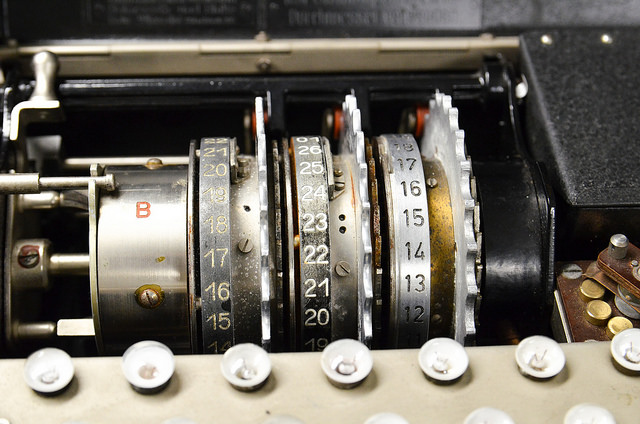

Inside the machine was a minimum of three rotors that would rotate every time a key was pressed to ensure that a different result was generated each time – even if the same key was pressed twice. There was also a plug board, which allowed the operator to add an extra layer of encryption.

In fact, between the rotors and the plug board, there were over 150 million million million (no, that’s not a mistake) possible combinations for each message intercepted by the Allies. Cracking it was a near impossible task, and for every day those messages weren’t deciphered, valuable supplies could be prevented from reaching Britain, and lives put at risk.

To provide an idea of exactly what the codebreakers were up against, we were recently lucky enough to get a peek inside an Enigma machine. Aptly, the machine was sent to the Alan Turing Building, where a series of X-ray radiographs were taken using X-ray Computed Tomography. These X-rays were then used to build a virtual 3D replica of the internal workings of the machine – providing a unique glimpse at the layers of mechanics that allowed messages to be so thoroughly encoded. You can watch a video of the 3D images here.

The machine’s owner David Cripps said: “One thing we’ve been able to do is actually look inside the rotors and see the individual wires and pins which connect the 26 letters on each of the three rotors, enabling a message to be encrypted. This is the first time anyone has been able to look inside the Enigma with this level of detail, using a technique that does not damage the machine.”

Cracking the code

Cracking the Enigma seemed an impossible task – and yet it was no match for some of the brightest minds of the time – and one Manchester hero in particular. Just one day after the UK declared war on Germany, mathematician Alan Turing reported for duty at Bletchley Park – the top-secret nerve centre for codebreaking during the war.

While there, Turing built a device known as the Bombe. This machine was able to use logic to decipher the encrypted messages produced by the Enigma. However, it was human understanding that enabled the real breakthroughs.

The Bletchley Park team made educated guesses at certain words the message would contain. For example, they knew that every day the German forces sent out a ‘weather report’, so an intercepted coded message would almost certainly contain the German word for ‘weather’. They also knew that most messages would contain the phrase ‘heil Hitler’. Looking for these patterns in the coded messages helped the team to calculate the daily settings on the Enigma machines.

Another breakthrough came with the discovery that numbers were spelt out as words rather than using the single letters on the machines meant to represent them (see image above). Learning this prompted Turing to go back and review any messages that had been decrypted, where he learnt the German word for one – ‘eins’ – appeared in almost every message. From this, he created the Eins Catalogue, which helped him to automate the crib process.

Weaknesses within the Enigma also helped the team to crack it. For example, a letter was never encoded as itself, which helped reduce some of the possibilities.

Not all the code-cracking efforts took place in Bletchley Park. When there was an urgent need to uncover certain codes, the RAF would assist the codebreakers by planting mines in areas the German forces had previously swept. This would prompt the German officers to send messages that contained words or phrases the codebreakers could recognise – known plaintext – which helped them to work out the machine codes.

Turing’s legacy

Thanks to the Bletchley Park team and the Bombe, the Enigma was cracked. And yet, such was the secrecy of the project, hardly anyone knew about this huge effort until three decades later – some 20 years after Alan Turing had died.

It is thought that the work of Turing and his team helped to end the war two years earlier than would otherwise have been the case – saving millions of lives in the process. Turing – who went on to take up the position of Reader at Manchester’s Mathematics Department – would not see this achievement recognised during his lifetime.

Gavin Brown, Professor of Machine Learning at The University of Manchester, said: “It is fantastic to unveil this new perspective on the Enigma in the Alan Turing Building, named after the man who played such a large role in cracking its code in World War II. Manchester was an environment where Turing flourished. His legacy can be seen right across the University, with researchers developing super computers that can model the human brain, exploring number theory and cryptography, as well as training robots to understand language. Right here, people are working on the principles that he laid down and the dreams that he had.”

Helping end World War II and saving millions of lives is quite a legacy – but why stop there? Alan Turing is, of course, also recognised as the father of modern computing thanks to his pioneering work in this area. He produced the first detailed design of a stored-program computer, and became the foremost expert in artificial intelligence during his lifetime. As if all that wasn’t enough, he was also an exceptional runner, and was occasionally known to run the 40 miles from Bletchley Park to London to attend meetings.

You may have heard that the Bank of England is calling upon the public to suggest scientists to appear on its new £50 note. There can be few people more worthy than Turing.

You can vote for who you think should appear on the new banknote here. Voting is open until December 14th, and your nomination must be a scientist who is now deceased.

Words – Hayley Cox

Images – School of Mathematics, Shaw June

Comments

3 responses to “Cracking stuff: how Turing beat the Enigma”

Thanks for the detailed and clear essay on Turing and cracking the Enigma coding machine. I’m a research psychologist working on how to empower neighborhood organizations to create local communities of indefinitely sustainable nature, as by refusing to use fossil fuels, or eat or sell red meat, eliminate fertile cats, control population growth, carefully screen police applicants, prohibit dictator leaders, etc. So , I’m having to “break” many “codes” of pessimism that threaten from every angle my vision of a sustainable planet earth. reading about individuals who have successfully “broken” implicit codes of pessimism (e. g. Wright brothers, Helen Keller, etc. ) keeps me going at age 82 and able to retire but enjoying ongoing challenges of my choice. I run 3 miles 3 times per week, split firewood, have assembled a battery of tests for screening police candidates, created a 15 dimension rating scale for placing politicians on the democracy/dictatorship continuum, etc.

No mention of Polish cryptographers who had been working on it for years before the war and broke the code and passed the knowledge to the French and the British. Sad.

Loved this article