Rocks in the African desert: fieldwork in Angola, part 2

Student experience Welcome to EES 29 October 2019

Dr Stefan Schröder continues his tale of an African adventure, covering the geologic process of rifting, desert camping and some surprising fossil finds. Part 1 can be read here.

We have set up camp between some of these granite inselbergs. A few kilometres west is the Atlantic, and in between the granite basement passes to Cretaceous rocks. These rocks formed when South America split from Africa in a process called rifting, about 130-120 million years ago. The resultant rift valley eventually widened into the present South Atlantic. It is these sediments we are interested in: dark weathered volcanics record the violent early stages of rifting. Directly above them are limestones, where warm fluids, interacting with granitic and volcanic basement, have come to the surface along faults, and precipitated so-called spring carbonates with a mounded topography. Younger rocks grace the landscape with brilliant red, yellow, white and brown colors. We try to understand how these rocks, and in particular the spring carbonates, relate to the structure of the basin, and the fluid flow in the South Atlantic rift. This tells us a lot about the processes driving development of such rifted margins.

This is remote desert country, and all has a sense of adventure: the tracks to the outcrops require 4×4 vehicles. In the evening we have a camp in the desert, and long discussions are held around a camp fire. Sleeping under the stars is my personal highlight of such a trip. The southern sky is beautiful at night – although many nights lack stars due to the coastal mist.

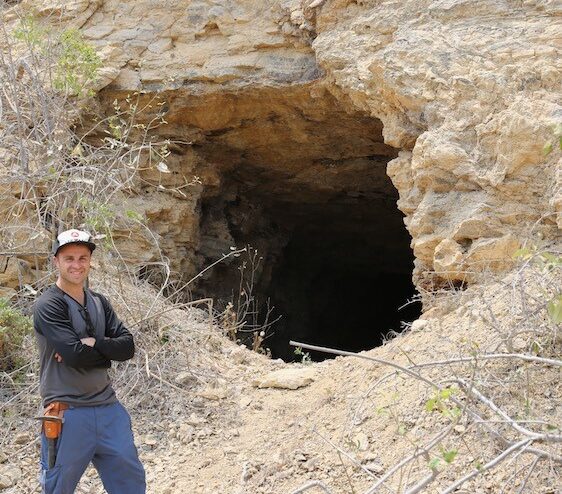

At various localities, limestones form m-scale mounded outcrops and terraces that sit on top of the granitic basement, or on the rift volcanics. Groundwater was heated up in the crust and by the volcanic heat flow, and where this water emerged at a spring, carbonate mounds and terraces formed. The groundwater was enriched in calcium carbonate, which precipitated due to degassing of CO2, and the drop in temperature at surface. The carbonates here also contain fractures filled with bitumen, which represents solidified hydrocarbons. It is possible that organic matter present locally in the rocks was heated due to local volcanism, and turned into liquid hydrocarbons that later solidified. The local population has dug shallow shafts and has literally mined the bitumen, probably for a long time.

The coastal area of southern Angola is famous among palaeontologists for its dinosaur fossils. Mosasaur skeletons were found here in Cretaceous deposits some 90-70 million years old. That was not the scope for our fieldwork – but we did pick up some dinosaur bones and shark teeth on the way back to the camp one day. To top it off, some of the spring carbonates contain tree trunks that fell down 120 million years ago, and were then fossilized by silica precipitation.

bitumencampingcarbonate moundsdinosaursfossilised tree trunkfossilsGeologygranite inselbergskerogenlimestonesmounded topographyPhDriftingsharkssolid hydrocarbonsstudyvolcanoes

Leave a Reply