In conversation with Dr Russell Garwood, Lecturer

Meet the Department 30 September 2019

I spoke to Dr Russell Garwood about everything from computational palaeobiology (his own coinage), to William Blake and black metal, to recreating evolutionary processes digitally, and, the new degree programmes in Earth and Environmental Sciences at Manchester.

Dr Russell Garwood and Dr Brian O’Driscoll happily facilitating the second year Geology field trip to Kinlochleven in Scotland. Students studied polyphase deformation of ~800 million year old sediments and conducted independent mapping.

Can you describe your research for the layman?

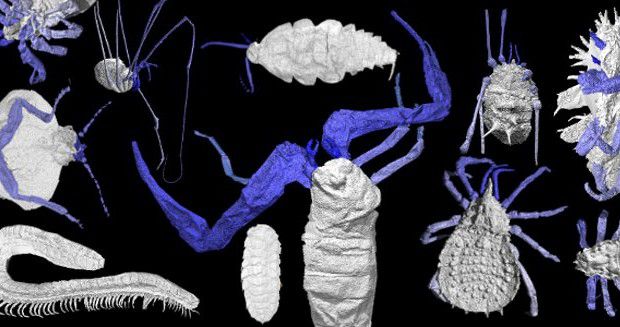

I study the evolution of life from its origin more than 3 billion years ago through animals around 300 million years old. I look at ancient life, so for me that includes things like the evolution of early single-celled organisms through to the evolution of some animal groups. I’m particularly interested in arachnids (spiders and scorpions are examples), and insects: two groups which make up the majority of known living species, and have a surprisingly rich fossil record. My research uses a range of relatively new techniques – or techniques that are relatively new to palaeontology: for example, I use high resolution CT scanning and computer-based approaches to help try and understand how different organisms relate to each other, and how we actually can derive those relationships better. I also look at evolution more generally using computer-based approaches – if I had to give it a name, I guess I’d call it computational palaeobiology. But I just made that up.

What A levels did you study?

I did A levels in Maths, Geology, Chemistry and Physics, and ironically, all of my research is basically biology!

How did that come about?

I always liked evolution, so I think it developed from there. My supervisor, Mark Sutton, was also influential, as he helped me realise that you could do cool things with computers and be a palaeontologist. And I always kind of liked playing with computers.

Who or what first inspired your interest in science?

I’m a palaeontologist, I work on ancient life, and the first time I really came across palaeontology as a subject was through a David Attenborough documentary in 1989 called Lost Worlds, Vanished Lives. For four episodes David Attenborough went around the world talking to people about dinosaurs, fossil preservation, or fossils from different periods in time, and it gave an overview of palaeontology as it stood in 1989. It was really, really cool – lots of people asking interesting questions. It was presenting the latest research of the time in a way that I could easily follow as a child, and I found it very inspirational. Indeed, it’s still good to watch now, and is available on DVD! Some of the ideas have stood the test of time, some of them haven’t, and it’s really interesting to see how the latter have changed and what has brought about that change. That’s the point at which I became interested in palaeontology, and then as a teenager I read a lot about evolution. At the time there was a court case in the US where creationism had just stopped being taught in schools, and the creationist movement changed to a thing called ‘Intelligent Design’ – I followed that with a lot of interest. My interest in evolutionary questions was kindled as a result of my interest in that debate.

CT-based reconstructions of various ~315 million year old land animals

What are your hobbies or interests outside of work, and do you have a favourite film, book or band?

For a long time, when I was doing my A levels and university degree until a few years ago, I actually worked as a music journalist – freelance – generally in the area of extreme metal. I listen to a lot of metal, and a lot of other genres, but with an interest in the more experimental end of music. I listen to music most of the time still (in my office, and even sometimes in meetings when allowed!), but I don’t do journalism anymore. My favourite band is a group called Ulver, who come from Norway, and they started off playing a genre called black metal, then they moved into folk, then a metal, jazz-influenced album that set the entirety of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-93) by William Blake to music, and they moved into (amongst other things) trip-hop, jazz, and synthpop. I also like films – I just got back from a film festival where I sat in a darkened cinema for 5 days straight and watched 25 films! I spend a lot of my free time watching movies. Favourite film is kind of hard to say, but I really like Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, it looks wonderfully atmospheric, slow moving, has got an amazing soundtrack, and it’s got a cool complex plot told in a non-linear way.

What are you working on at the moment?

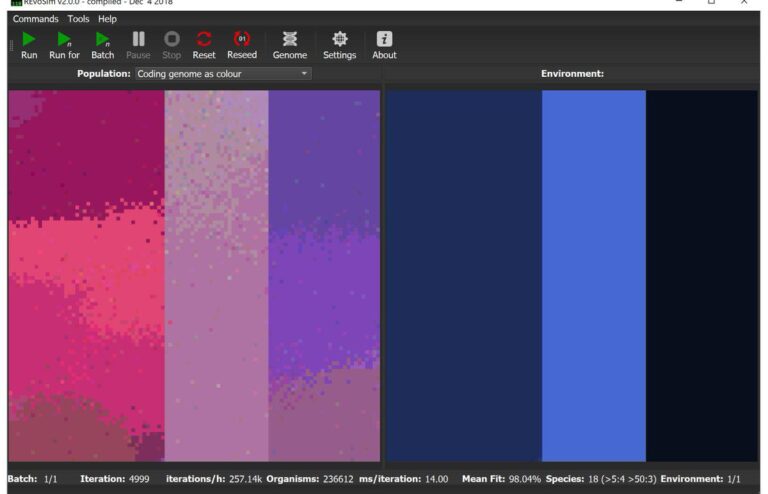

I’ve got a wide range of projects ongoing, but one I’m really excited about at the moment is with some colleagues at Imperial and here at Manchester – we’ve recently released some software that simulates evolution, so we can actually look at evolving systems within a computer, and then study how evolution happens over really long time periods with large population numbers. So suddenly, all of the things that we can’t easily address by looking at living systems can be investigated. This is because, for example, one way to study evolution is to look at a model organism, a famous one is the fruit fly Drosophila. But you can’t look at how evolution happens over geological time periods in the lab because model organisms don’t breed fast enough. And when you use the fossil record to look at how evolution proceeds there are lots of biases whose impact we generally don’t fully understand, and thus it is hard to correct for them. For example, not everything fossilises, and where and what does fossilise overlays patterns on what might otherwise be an easier-to-read history of life. As such, it’s really difficult to look at some of these deep time questions. So the idea behind this software is that we can have a really simplified, quite abstract system, but one in which we can see evolution happening over geological timescales. We can use this to try and look at things like how species separate from each other (i.e. how speciation occurs). How things like sexual reproduction originated is similar. That you’ve got to have males and females as with so many animals and fungi and plants is a system many organisms use, but we don’t really fully know why it is so common. Hopefully we can apply our findings to the real world as well – so that’s really exciting.

Screenshot of simulation software from the evolution simulation project.

Can you talk to me about the degree programme changes at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Manchester, and why people should consider studying here?

I think it’s really, really exciting – we’ve got a broad Department. We have academics working on everything from, for example, groundwater pollution to atmospheric physics, all the way through to people looking at volcanoes and how rocks bend on a large scale. The new degree programmes actually encompasses this really wide range of expertise, so there are people that are able to teach their specialism on each one of our degree Pathways. I am going to be teaching on the Palaeobiology Pathway, for example. If you’re interested in ancient life, this is a really exciting opportunity for us to tell you all about the many topics that we research here at the University of Manchester, and all the vital and deeply interesting questions to which science doesn’t yet have an answer. Our group is strong on, for example, applying novel techniques to understand fossils. Examples include X-ray analyses of fossils, and understanding patterns in evolution. What’s nice about all of these topics is that in the current state of the field, within a three year degree we can teach to a point where our students will be completing their third year dissertations on subjects that are actual unsolved questions – people don’t fully understand many really significant processes. Because the degree projects will actually be addressing one of these really exciting questions, they’ll be breaking new ground in science. To be the first person to uncover something about, for example, the relationships of a 400-million-year-old animal, is really fantastic. For that reason, I think our new degrees are really exciting.

Follow Russell on Twitter @RussellGarwood and check out his website.

Russell also tweets for @ICALManchester and updates the website as a member of ICAL (The Interdisciplinary Centre for Ancient Life).

Interview conducted by Jemma Stewart.

black metalcomputational palaeobiologyearth scienceearth science mattersEvolutionPaleobiologysimulated evolutionundergraduatewilliam blake

Leave a Reply