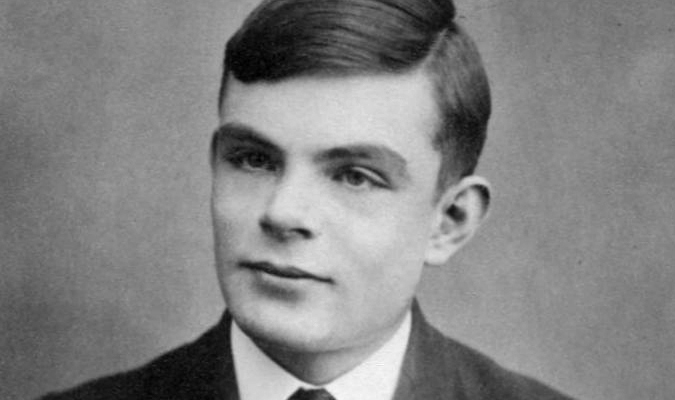

Recently on our blog we delved into a lesser-known side of Alan Turing: his philanthropy. It got us thinking about what else people might not know about the maths genius who helped develop modern computing at The University of Manchester. So we did a little research – and this is what we found…

Exceptional promise

Turing’s abilities were evident from a young age. Speaking of the then-nine-year-old, his headmistress at St Michael’s Primary School in Hastings stated: “I have had clever boys and hard-working boys, but Alan Turing is a genius.”

His interest in chess began at Hazelhurst Preparatory School, where he spent hours alone solving complex chess problems. Later in life he would be credited with designing the world’s first computer chess program: Turochamp.

Aged 13, Turing headed to Sherborne School, a boarding school in Dorset. His very first day, however, fell within the nine-day General Strike of 1926, scuppering his chances of attending. Undeterred, the teenager raced off for school on his bike – and rode the 60 miles from Southampton to Sherborne alone, stopping overnight at an inn.

Physical prowess and determination

It was far from the only time his physical prowess and determination would impress. In fact, he was an avid long-distance runner – and was so good that he tried out for the 1948 British Olympics team. Hampered by injury on the day, he didn’t qualify for the team; yet his marathon tryout time was only 11 minutes slower than that registered by British silver medallist Thomas Richards.

Turing ran to relieve the stress of his work, and was even known, during his time at Bletchley Park, to run up to 40 miles for meetings in London. Members of Walton Athletic Club invited him to join their club after he overtook them a few nights earlier, noting his exceptional speed and hard, grunting style. While at King’s College, Cambridge, Turing ran along riverside footpaths between Cambridge and Ely; the annual ‘Turing Relay’ would later be held there in his honour.

He enjoyed rowing and sailing, and continued to cycle – often riding his bicycle to and from Bletchley Park. Colleagues would later recall a fault with his bike that meant the chain regularly fell off – rather than getting it fixed, however, he figured out how to correct it on-the-move, and counted the number of times the pedals went round before adjusting the chain by hand. A sufferer of hayfever, Turing was also known to cut an especially peculiar figure in the first week of June each year, when he would cycle to work in a gas mask to keep the pollen away.

The eccentric ‘Prof’

The eccentricities didn’t end there. He was called ‘Prof’ by colleagues at Bletchley Park, and ‘Prof’s Book’ was the name given to his works on the Enigma. Turing was also said to have chained his mug to the radiator pipes, preventing anyone else from using it.

While at Bletchley Park he proposed to a woman named Joan Clarke, a colleague in Hut 8. Clarke, also a mathematician and cryptanalyst, agreed to the marriage. The engagement did not last, however; Turing revealed his homosexuality and couldn’t proceed with the wedding. Perhaps the revelation wasn’t too much of a shock to Clarke, though, who was said to be ‘unfazed’ by the admission.

Turing joined The University of Manchester in 1948, taking up a role as Deputy Director of the Computing Laboratory. And it was in 1950 that, in a famous paper entitled Computing Machinery and Intelligence, he first addressed the issue of artificial intelligence – or AI.