Supermassive black holes to rock (\m/) time and space

Departments Research impact and institutes 3 March 2022

“You set my soul alight” croons Matt Bellamy on hard rockin’ 2006 Muse single Supermassive Black Hole.

And now, in 2022, researchers – including here at The University of Manchester’s Jodrell Bank – have discovered another bombastic performance set to rock time and space: a cosmic dance of not one but two giant black holes, in the very heart of our galaxy…

Dancing in the dark

“This is a mind boggling story that has been 45 years in the making,” explains Professor Keith Grainge of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics and the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

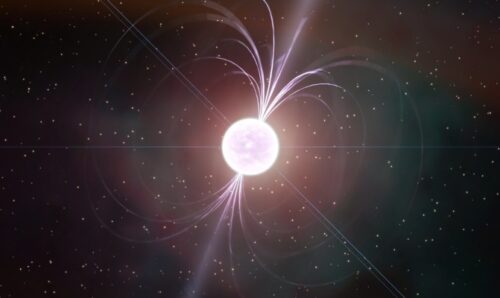

“Nine billion light years away there are two monster black holes, each many millions of times more massive than our Sun, orbiting around each other. We can see this with radio telescopes because one of the black holes is emitting a radio jet towards us and we see it brightening and fading as they rotate one another.”

The two black holes are locked in a cosmic dance of epic proportions. They’re the tightest-knit supermassive black hole duo ever observed – yet are separated by a distance roughly 50 times that between the Sun and Pluto.

It’s the first time such a ballet, where the duo appear to orbit around each other every two years, has been observed. And it’s only the second-ever candidate pair of merging black holes; the first a quasar called OJ 287, circling every nine years.

Shake, rattle and roll

The stellar research has been published in The Journal of Astrophysical Letters, and considers evidence spanning almost half a century.

Professor Grainge’s involvement stretches back to 2006, when he helped with recommissioning the OVRO-40m telescope. “Since then I have been involved with a programme of using the OVRO-40m to monitor the radio flux of ~1500 blazar candidates (a blazar is a particular type of active galactic nucleus, AGN) every three or so days,” he shares.

“One of these sources turned out to have this interesting periodic variability, which makes it a good candidate for a binary supermassive black hole system.”

This cosmic waltz is taking place within a quasar – not the laser quest-style shoot ’em up we enjoyed as children – but the active, energetic cores of galaxies. In some quasars, the supermassive black hole creates a jet that shoots out close to the speed of light.

The Clash

The quasar in this new study has been named PKS 2131-021 and, because its jet points towards Earth, forms part of a quasar subclass called blazars.

Studying this blazar has helped astronomers in their bid to prove the theory that quasars could, in fact, possess two orbiting supermassive black holes.

Radio observations of PKS 2131-021 have indicated that a powerful jet emanating from one of the two black holes is shifting back and forth, and that this is due to the pair’s orbital motion – causing periodic changes in the quasar’s radio-light brightness.

Sandra O’Neill, lead author of the study and an undergraduate student at Caltech, the California Institute of Technology, says: “When we realised that the peaks and troughs of the light curve detected from recent times matched the peaks and troughs observed between 1975 and 1983, we knew something very special was going on.”

Likening the movement of the jet back and forth to a ticking clock, Professor Tony Readhead, also from Caltech, adds: “The clock kept ticking. The stability of the period over this 20-year gap strongly suggests that this blazar harbours not one supermassive black hole, but two supermassive black holes orbiting each other.”

The two are expected to collide eventually and, when they do, the event will send gravitational waves across the Universe.

It’ll likely be another 10,000 years, however, before we have to face that particular music…

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with the latest posts from The Hub.

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Shutterstock, Caltech, The University of Manchester