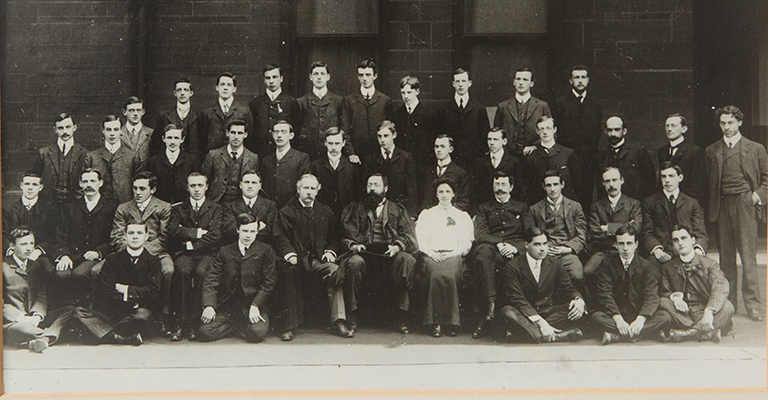

Walking along the fourth floor of the Chemistry Building, Dr Kristy Turner‘s eyes were drawn to a figure in an old class photo. On the front row, among a sea of men in dark suits, sat a woman in a white blouse.

Her interest piqued, Dr Turner wanted to find out more about the intriguing woman – seemingly the only female in her 1905 graduating class.

The story of Rona Robinson, she would discover, was a fascinating one.

“Rona was a pioneer in science and in society,” Dr Turner, a chemistry teacher at both the University’s Department of Chemistry and at Bolton School, explains. “She came from a working class background, but what she did forged a path for so many women who followed in her footsteps. She never married and had no children and I can find no other relatives, so I feel a little like the custodian of her story.

“She didn’t travel the world or win a big international prize, in many ways she led a very ordinary life as a chemist – and this in itself is important.”

Not so ordinary, however, is the fact Robinson was the first woman in the UK to earn a first-class degree in chemistry. She graduated from Manchester in 1905, receiving the LeBlanc medal for distinction in organic chemistry, as well as a Mercer scholarship for the best final-year student entering research. She would also stay at Manchester for her MSc, which she completed in 1907.

Later, as a synthetic chemist in the dyes industry, she would go on to work for Manchester firm Clayton Aniline (later taken over by modern firm Ciba), and there are several patents that bear her name.

But, as Dr Turner points out: “Scientists are not just scientists; their lives extend and influence beyond labs.”

For Robinson, this would be as part of the suffrage movement.

Suffragettes and hunger strikes

“Rona met Dora Marsden, a prominent suffragette, when she was in teacher training,” Dr Turner notes. “They both resigned their teaching posts to become paid members of the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union), the organisation headed by Emmeline Pankhurst.

“Throughout 1909 she was an active suffragette, even carrying out a protest at the opening of chemistry laboratories at the University. She was imprisoned a number of times and went on hunger strike.

“Force feeding during her first hunger strike permanently damaged her health – she actually gave up suffrage work as she was exhausted, settling down to life as an industrial chemist.”

Robinson was presented with a Hunger Strike Medal by the WSPU – one of no more than 100 awarded – and the two bars on the medal are believed to signify the two separate hunger strikes she endured (a tactic used by prisoners to secure release on medical grounds). While the medal was sold to a private collector in the US, a WSPU banner unfurled in 1908 by Robinson and her fellow suffragettes is now displayed in the People’s History Museum.

For Dr Turner, one thing became clear as she dug deeper into Robinson’s story: more people needed to hear it.

Wikipedia and gender bias

When she first spotted Robinson’s picture, Dr Turner took a photo and tweeted about the mysterious woman, hoping the Twittersphere could help her learn more. A helpful contact replied with a Wikipedia link; only it was a short, “stub” of an article.

Inspired by the work of Dr Jess Wade, who has been on a mission to better represent women and black and ethnic minority scientists on Wikipedia, Dr Turner decided to bolster the entry herself.

“Wikipedia is always one of the first hits when people search the internet. Jess Wade has been a Wikipedia writing machine, trying her best to change the gender bias that exists in scientific biographies on Wikipedia. I could never match her for energy and output but I wanted to do my bit and make sure Rona’s Wikipedia entry was as full as I could make it.

“I have always been interested in the history of science and I found my work on Rona absolutely fascinating, it kept me up late at night carrying out web searches and I spent many hours in the family records at the Central Library.”

And we’re so glad she did.

Since Dr Turner started her research into Robinson, a poster display about the latter’s life now stands proudly in the concourse of the Chemistry Building – the same building where the former’s interest began. It was discovered that Robinson left a legacy in her will to provide an award for female postgraduate students; this has since lapsed, but Dr Turner is hoping to revive an award in her honour very soon.

Rona Robinson’s story is striking not only because she was the first woman in the UK to earn a first-class degree in chemistry. Nor because she was an important cog in the suffragette movement. Her tale really resonates because she was an ordinary woman, from a working class background, who worked hard and fought for what she believed in.

“I think in science we tend to have a hero complex, we talk a lot about big names and big discoveries,” Dr Turner adds. “Many of our graduates will go on to have very ordinary lives in science, in industry, academia and other careers. We need to talk more about that.”

We couldn’t agree more.

Hear Dr Turner talk more about Rona Robinson on The Buzz: A science and engineering podcast.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with the latest posts from The Hub.

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Kristy Turner, Dave Guttridge