What a month for Jodrell Bank.

The historic site – owned by The University of Manchester – has been named a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the Square Kilometre Array Global Headquarters have been formally opened at the location. It now looks ahead to celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Moon landings. There’s also the small matter of Bluedot Festival.

Bluedot is an event that’s grown in stature year on year, with huge names in science and music appearing before the unique backdrop of the Lovell Telescope – and this year sees no less than Hot Chip, Kraftwerk and New Order taking the stage. Resplendent in white and instantly recognisable, the Lovell Telescope is a 250 ft structure that wouldn’t look out of place in a Star Wars film.

But what of the name? Is that instantly recognisable? Do you know what – or rather who – it’s named after?

Recently on The Hub we’ve looked at a number of University buildings that take their name from people of distinction; to the Lovell Telescope is where we turn next.

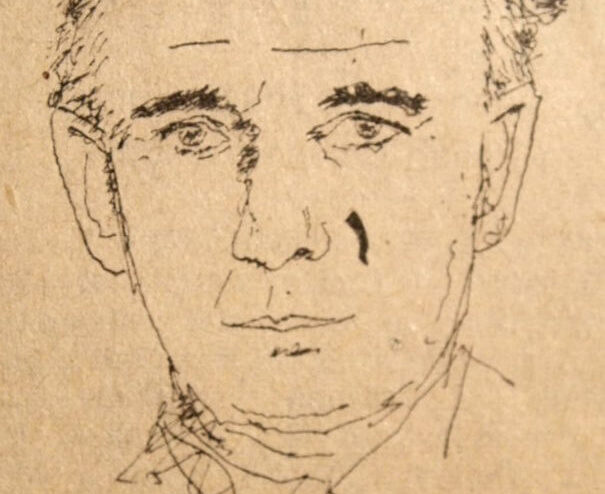

Sir Bernard Lovell

The telescope is named after Sir Bernard Lovell, a man who worked here at the University, helped build the structure itself and served as Director of Jodrell Bank Observatory from 1945 to 1980. He may even have been the subject of a Cold War assassination attempt. An astonishing story for a man who enjoyed the quiet life – he loved cricket and played the organ at his village church well into retirement.

Cricket and music, it seems, were in Lovell’s blood. His mother came from a family of cricketers and played the game herself, while his father, a local businessman and Methodist lay preacher, was a keen musician. Lovell’s interest in science, however, would first be ignited at the age of 15 when at a public lecture he witnessed AM Tyndall, Professor of Physics at Bristol University, project an electric spark across – what seemed to him – an impossibly large gap. Young Bernard was hooked.

He arrived at Manchester after receiving from Bristol University a first-class degree in physics and a PhD on the conductivity of thin metallic films. He worked in the cosmic ray team at The University of Manchester until the outbreak of the Second World War, when he worked – like fellow famous Manchester names and builders of the Manchester Baby Tom Kilburn, FC Williams and Geoff Tootill – for the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE).

Here he helped develop aircraft radar systems and assisted during the recovery of the secret cavity magnetron (a device that made radar sets smaller to allow aircraft and ships to locate submarines) following the crash of the Handley Page Halifax heavy bomber. A number of Lovell’s colleagues had died in the tragedy.

Some of us are looking at the stars…

Lovell resumed his work into cosmic rays after the war. Now, we all know how busy Oxford Road can get – the hustle and bustle of rushing students, the rumblings and beeps of buses – and seemingly it was no different in Lovell’s day. In fact, background interference from the road’s electric trams disrupted Lovell’s work so much that he went in search of a quieter, more remote location. His search took him to Jodrell Bank in Goostrey, Cheshire.

The site takes its name from a nearby rise in the ground, itself named after one William Jauderell, an archer in the armies of Edward ‘the Black Prince’ of the 14th century – one of the greatest knights of his age. The area was previously used by the University’s Department of Botany but, using equipment left over from the war, Lovell would establish it as an important centre for astrophysics.

Construction of the Lovell Telescope began in 1950 (its motor system used part of the gun turret mechanisms from the battleships HMS Revenge and HMS Royal Sovereign) and it eventually went into operation on 2 August 1957. There had been money concerns based on worries over structure, with two large radio telescopes in other parts of the world having recently collapsed. But despite other delays and escalating costs, the telescope was finished in time to track the first artificial satellite, the Soviet Union’s Sputnik 1. It was the only instrument able to do so.

The Lovell Telescope was the then-largest steerable radio telescope in the world and was used to track both Soviet and US probes aiming for the Moon in the 1950s and 1960s. Initially known as the ‘250 ft telescope’ or the Radio Telescope at Jodrell Bank, it would become the Mark I telescope around 1961 and finally the Lovell Telescope in 1987. A year later it became a Grade I listed building.

An iconic structure

The telescope has survived the incessant Manchester rain and even the infamous Gale of January 1976 – a storm that killed 24 people in Britain and 82 across Europe. It was so powerful that it caused the telescope’s towers to bow and one of its bearings to slip. It has also survived the very real nuisance of pigeon droppings – thanks to peregrine falcons that nestle in each of its two support towers.

With its impressive structure and picturesque surroundings, the telescope presents an arresting backdrop. The bowl has played host to three bands’ videos, including Placebo’s The Bitter End, Public Service Broadcasting’s Sputnik and Party Up the World by D:Ream – the band for which The University of Manchester’s celebrated physics professor Brian Cox famously played keyboard.

The telescope has also featured in Doctor Who and the film version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and was visited by Coronation Street icon Rita Fairclough in a 1981 episode of the timeless Manchester soap.

Speaking of popular culture, readers of a certain age may also be interested to learn that the fictional scientist Bernard Quatermass – the star of various BBC sci-fi serials in the 1950s, known for his great intelligence and portrayed in a 2005 remake of The Quatermass Experiment by Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels actor Jason Flemyng – was given his first name in honour of Lovell.

Pursuing the quiet life

Perhaps akin to something from an on-screen thriller, it has also been suggested that an attempt on Lovell’s life was made during a visit, in 1963, to the Soviet Deep-Space Communication Centre – after which Lovell fell mysteriously ill. The full truth may never be known, but the University has previously published online Lovell’s diaries from the visit.

The incredible episode is at odds with the apparent much quieter, incident-free years of Lovell’s later life, when he lived in the English countryside, spent time with family, listened to music, read books and enjoyed the arboretum he had created at his home. Any visit to Jodrell Bank today should include a walk around the site’s own arboretum, a wonderful remnant from the location’s botanical past.

Jodrell Bank will forever be indebted to the work, vision and brilliance of Sir Bernard Lovell. And his influence will never be forgotten, not least through the magnificent telescope that bears his name. It’s only right that during one of the site’s proudest months we remember a man who did so much in the name of discovery – in this world and beyond.

Words: Joe Shervin

Images: Jodrell Bank, The University of Manchester, Wikimedia Commons

Be sure to subscribe on our homepage to keep up to date with all the latest posts from The Hub.