The School of Physics is the proud holder of an Athena Swan Silver Award. This award recognises the advancement of gender equality in science, technology, engineering, maths and medicine (STEMM) employment, research and education.

Nationwide, just 20% of students studying Physics at degree level are female. At The University of Manchester, this figure is higher – with women making up one in four of the places on our undergraduate degree. For this we have been awarded a Silver Award by Athena Swan – but there is still work to be done. As the School of Physics and Astronomy’s Prof Stephen Watts told the audience of this month’s Ada Lovelace Day event: “We don’t stop here.”

Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell, the University’s President and Vice-Chancellor, also pointed out that when it comes to hiring staff, appointments are based on merit and ability. Simply put – the chance of you getting a job here depends on your knowledge of Physics, not your gender.

So why are women so under-represented in this field of study? And when does the problem start?

Removing gender from the conversation

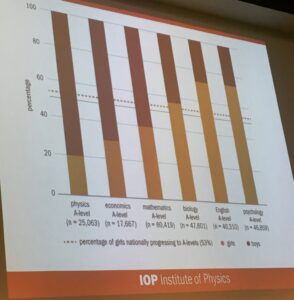

One of the event’s speakers, UoM graduate and North West Regional Officer for the Institute of Physics (IOP) Hannah Renshall, believed the problem might start in the playground. She shared interesting knowledge compiled by the IOP, including that girls make up just 20% of Physics A-level students nationwide, compared to more than half of Biology A-level students (see diagram above).

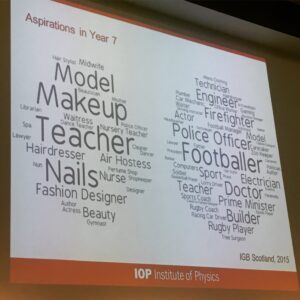

And the problem may stem back to an even earlier age. Asked what their aspirations were at age 11 and 12, girls and boys already had very different ambitions:

Hannah noted that we are all guilty to some extent of unconscious bias. For this reason, she noted that it’s time to “remove ‘male’ and ‘female’ [labels] from the conversation”.

“You deserve your place”

Attendees also heard from alumni Stephanie Baines, who’s currently studying for her PhD at King’s College London, and Malin Litwinski, Physics graduate and now Junior Consultant for a software company.

Stephanie revealed she decided to study Physics at degree level because “I wanted to understand things at a fundamental level”. But in spite of being incredibly gifted at her subject, she still battled with a lack of confidence in her abilities. To combat this, she threw herself into the Societies side of the University, and got involved with our PASS (Peer Assisted Study Sessions) scheme.

After graduating, Stephanie took a gap year on the advice of her parents and spent the time skiing in the mountains. She said this helped her get to know a different side of herself. Today, Stephanie is working on her PhD in addition to assisting on the MoEDAL experiment to search for the highly-ionising particles produced in high-energy collisions at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.

Malin studied Physics alongside Stephanie and also battled a lack of confidence in her own abilities. She told the event’s attendees that she was filled with self-doubt and a sense of “imposter syndrome” when she began her degree, after being voted ‘the most likely to win a Nobel Prize’ while at school.

At university, Malin founded the WISE (Women in Science and Engineering) Society. She also became more accepting of her own position and abilities, telling attendees: “You’re already here so you do deserve your place at the table.”

Both Stephanie and Malin recognised that there is an issue with women being under-represented in certain scientific disciplines, like Physics. Stephanie pointed to statistical research that suggests women are less confident in promoting themselves and their abilities, and so miss out on key opportunities for advancement. “We are trying to bring equality and deal with a statistic that shouldn’t be there,” she said.

Making a difference

There is plenty being done to raise the profile of women in STEM and encourage more girls to choose to continue studying Physics at degree level. Janni Harju and Charlie Campion both work with STEMSoc to get young people excited about science. Their aim is to get kids “dreaming outside the box”.

And an early interest in science can lead to amazing career opportunities in the future. Ioanna Koutava is a diversity analyst at CERN. She told the audience that women account for just 20% of the professionals employed at the organisation – a figure that mirrors the number of young women choosing to study Physics at degree level in the UK. She also noted that this figure reflects the number of women applying for positions at CERN (just over 20% of applicants are women).

Ioanna warned of the “leaky pipeline” – a problem that suggests the scientific community is losing female voices from the point of higher education and onwards. And the steepest drop appears between female PhD graduates and researchers.

Thankfully, whether it’s through the work being done by societies like STEMSoc and WISE or by the University and initiatives like Athena Swan, this trend is improving. UoM’s School of Physics and Astronomy now has its highest percentage of female undergraduate students ever – and is not slowing its efforts to improve this figure yet further.

And the reality is, more female minds and voices within the scientific community benefits everyone – just as Alan Turing discovered when he came across the notes compiled by a female scientist almost a century earlier.

Who was Ada Lovelace?

Ada Lovelace is often noted as being ahead of her time – she was a woman whose keen interest in science was encouraged, which was rare at the turn of the 19th century. But science was far from a hobby for Ada, and her notes were instrumental in the development of modern day computing. As she died more than 80 years before the invention of what is considered to be the first programmable computer, that’s quite some feat.

The daughter of the infamous poet Lord Byron and his strict and devout wife Baroness Wentworth, Ada was passionate about science from an early age. Her parents parted ways when she was just a baby, and her mother worked hard to instil in her a love of logic.

Ada was a gifted mathematician, but she was also interested in engineering. She had a strong desire to fly, and went about working out if it was possible for a human to do so with scientific precision.

At the age of 18 she was introduced to Charles Babbage – a mathematician, inventor and philosopher. Babbage had designed the Analytical Engine – a theoretical general-purpose computer. Ada was fascinated and wrote in detail on the potential of the machine if it was built. She suggested it could be used to create music and complete other tasks. Most pointedly, Ada published ideas for what we would now call computer programs, leading many to now credit her as the world’s first computer programmer (although others contest this claim).

Whatever your own opinion, her role in the history of computer science can’t be diminished. Our own Alan Turing worked from her notes when he was carrying out his own work in this field nearly a century after Ada died.

And Ada Lovelace is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to women who have made instrumental breakthroughs and discoveries within the field of science. This is just the start of things to come – learn about our own Women of Wonder here.

Words – Hayley Cox

Images – The University of Manchester, Aristocrat