Nuclear in Taiwan

Uncategorised 20 June 2025

This blog post is the second part of a series detailing this trip, contributed to by students partaking in this trip.

With the supply of fossil fuels at risk due to geopolitical factors, electricity demands rising and a greater push to reduce carbon emissions across the world, countries must reconsider their approaches to energy generation and security. Unlike other countries across the world which can drill for oil or natural gas or mine for coal, the Republic of China (ROC) does not have large reserves of natural resources. As such, it must depend on importing about 96.19% (in 2023) of its energy [1], which is susceptible to disruption. However, this did not use to be the case.

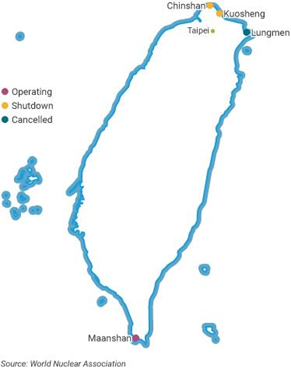

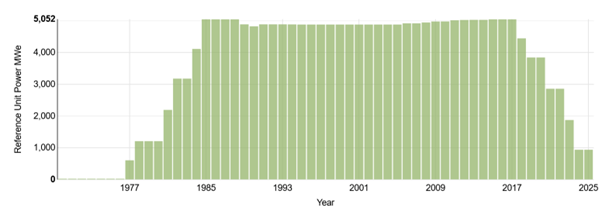

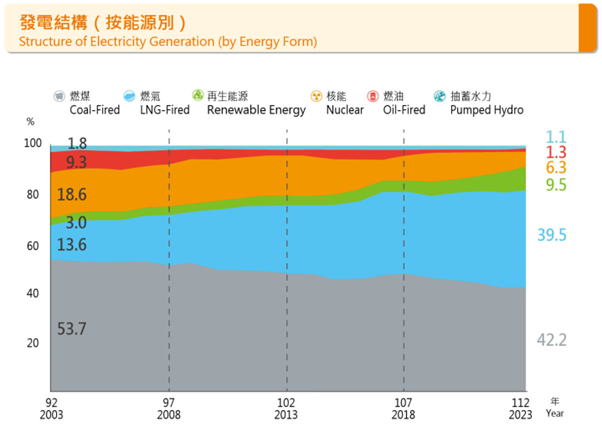

Rapid industrialisation and economic growth (also known as the Asian Miracle) in the 1960-70s resulted in the construction of 3 nuclear power plants (NPPs) with 2 reactors each to meet energy demands. These were at Jinshan/Chinshan (BWR, 1972), Kuosheng (BWR, 1975) and Ma’anshan (PWR, 1978) (Figure 1). These all used Uranium Dioxide fuel pellets, an open fuel cycle and the low-level waste produced is stored on an island off the coast of the ROCs southern tip called Orchid Island. At its peak in the 1980s, these reactors provided 52.4% of all energy consumed in the ROC [2] and operated for a long period as shown in Figure 2. A fourth nuclear plant at Lungmen also began construction in 1999 but was delayed due to opposition. However, following the March 2011 Fukushima Dai-Ichi accident, a new national policy in November 2011 affirmed that the operational licenses for all reactors would expire after 40 years and nuclear power would be gradually phased out [3]. This policy was further reinforced when the Democratic Progressive Party was elected to power in 2016 and re-elected in 2020 and 2024. Their platform included phasing out nuclear power by 2025, switching to more renewable and natural gas sources which has slowly happened over the last 20 years ( Figure 3). As such, only one reactor remains operational providing 938MW at the Ma’anshan NPP with its operational license expiring in 2025 [4]. The Lungmen NPP project remains suspended indefinitely after a referendum in 2021 rejected restarting construction of the plant.

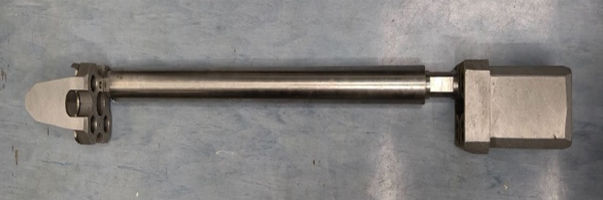

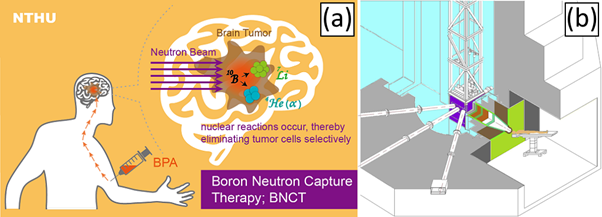

Despite the government’s policy on nuclear power, research continues at the last remaining research reactor at the National Tsing-Hua University (NTHU). The Tsing-Hua Open-Pool Reactor (THOR) is TRIGA (Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomics) reactor and was the first nuclear reactor to operate in the ROC, achieving its first criticality in 1961. It first used Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) fuels but in 1977 this was slowly replaced by Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) TRIGA fuels, a model of a fuel assembly can be seen in Figure 4. Initially this reactor was used to research the performance characteristics of nuclear reactors as well as train nuclear reactor operators across the ROC so they could have operational experience prior to the construction of other nuclear reactors. As time went on, this research expanded to producing the radioisotope Iodine-131 for medical use, but the currently the main purpose of THOR is for Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (Figure 5). A Boron containing drug (e.g. p-boronophenylalanine/BPA) is injected into the target tumour, then the THOR reactor is operated to produce a low energy neutron beam that is targeted at the patient. The boron captures the neutrons, undergoes decay and using this nuclear reaction, only the tumour is selectively damaged. Currently it is used as an experimental treatment as one of the final options for patients with final stage cancers, but it has had a high success rate.

Appetite from the public and government for future nuclear power plants has diminished and despite the closure of the other 5 research reactors across the ROC, THOR continues to operate. It has had its operational license extended further, carrying out vital research and treatment of patients using BNCT. In comparison, the Ma’anshan NPP’s operating license is due to expire in May 2025 and then decommissioning of the ROC’s last NPP will begin. Whether or not nuclear power will make a resurgence in the ROC given energy security concerns and geopolitical climate remains to be seen.

Bibliography

[1] Ministry of Economic Affairs Energy Administration, “Energy Statistics Handbook 2023,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.moeaea.gov.tw/ECW_WEBPAGE/FlipBook/2023EnergyStaHandBook/index.html#p=9 . [Accessed 26 02 2025].[2] S. M. Gorska, “Nuclear Safety and Energy Security in Taiwan: A Divided Society,” Global Taiwan Institute, [Online]. Available: https://globaltaiwan.org/2024/09/nuclear-safety-and-energy-security/. [Accessed 23 02 2025].

[3] Atomic Energy Council Executive Yuan, “The Republic of China National Report For the Convention of Nuclear Safety,” Atomic Energy Council Executive Yuan, [Online]. Available: https://www.nusc.gov.tw/share/file/regulation/Z8sqF38NEH-s7XQcuAroCw__.pdf. [Accessed 23 02 2025].

[4] World Nuclear Association, “Nuclear Power in Taiwan,” World Nuclear Association, [Online]. Available: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/others/nuclear-power-in-taiwan. [Accessed 20 02 2025].

[5] National Tsing Hua University, “NTHU’s Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Center Begins Treating Overseas Brain Cancer Patients,” National Tsing Hua University, 02 03 2023. [Online]. Available: https://nthu-en.site.nthu.edu.tw/p/406-1003-181203.php. [Accessed 2025 02 20].

[6] S. Jiang et al., “The overview and prospects of BNCT facility at Tsing Hua Open-pool reactor,” Applied Radiation and Isotopes, vol. 161, 2020.

Leave a Reply